Growing up on Tasmania’s North West coast, Zoe Rimmer recalls a quiet childhood. Her pataway (Burnie) home showered her with spectacular coastline spawning a deep connection to the ocean. Special time spent at pinmatik (Rocky Cape) is etched in Zoe’s mind, connecting with culture and being a part of the Aboriginal community’s drive to advance the land rights movement.

To the north east, Zoe could sense the presence of the remote islands that lay beyond her gaze. In the early 1800s the British discovered the rich bounty that lay amid the wild Furneaux Group. The gluttonous sealing trade exploded, sending shockwaves not only through the seal population but through local Aboriginal tribes. The abduction of Tasmanian Aboriginal women was common and settlements grew dependent on their labour. Heartbreaking reports of the time indicate that their treatment was often akin to slavery, or worse.

Zoe’s grandmother was born on Flinders Island and grew up on the remote outpost of Cape Barren. Descended from Pularilpana (Pollerrelberner), Zoe explains, “Pularilpana, along with several other Aboriginal women, was abducted from the north east in the early 1800s and sold off for a life on the islands. She eventually partnered with sealer Edward Mansell – a union that saw the continuation of the Aboriginal bloodline.”

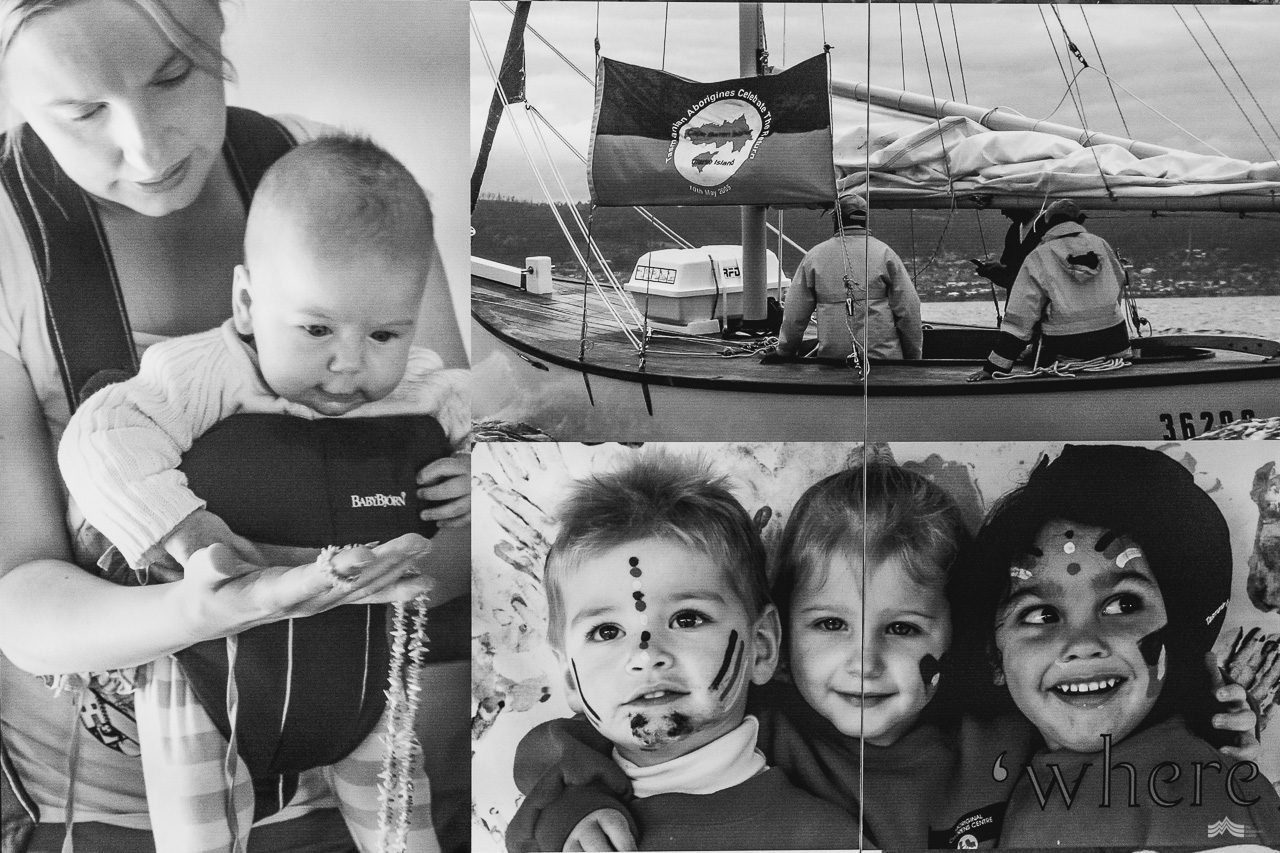

“Cape Barren Island was an Aboriginal Reserve from the 1880s until the 1950s,” continues Zoe. “Throughout this time the government in Hobart and, in fact, the exhibitions at the state museum, were denying the very existence of Tasmanian Aboriginal people. My nan’s generation suffered the overt racism of segregation, assimilation and the welfare system. My mum, aunts and uncles generation were part of a larger movement of Aboriginal activism, becoming politically organised through the establishment of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) in the early 1970s. My family have always known and been proud of who we are and where we come from. I’ve been lucky to learn through my Elders and in turn am passing practices like basket weaving and shell stringing on to my own daughter.”

This proud Pakana (Tasmanian Aboriginal) woman is grounded in a rich sense of history. Today, as Senior Curator for First Peoples Art and Culture at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), Zoe stands tall for Tasmanian Aboriginal knowledge and spirit. With dreams that stretch back through the ages and with a strong connection to Country, she is a shining light for sharing stories and reconnecting cultural links.

As a young woman, Zoe’s university studies saw her study fine arts, majoring in design. Then in 2003, a traineeship at the museum shifted her focus. “My studies changed to combine Fine Arts with Aboriginal Studies and History,” she explains. “My traineeship was primarily in Business Administration but I had the opportunity to work under the first ever Senior Curator of Indigenous Cultures, Tony Brown. I finished both my traineeship and degree under him and we co-curated the first Aboriginal led permanent gallery at TMAG, ningina tunapri: to Give Knowledge and Understanding.”

Fast forward twenty years and Zoe herself holds the very same curatorial role that Tony once did. A sense of rebirth prevails however, signalled by the change of name to Senior Curator of First Peoples Art and Culture – a more fitting description of the work currently underway. Zoe represents the new generation of Aboriginal leaders within Australia’s contemporary museum sector. Leaders who are working at the forefront of the global movement to return objects of significance to their communities of origin.

“We have an incredible First Peoples collection here in Lutruwita (Tasmania),” describes Zoe with bright enthusiasm. “They say that only one or two percent of a museum’s collection is ever on display at once, and I would say that’s about right here too. Our collection includes special Tasmanian artefacts but also those belonging to other cultures. If you turn the clock back about 200 years, it was common that missionaries would call in to Hobart on their way through the Pacific. As a result, the First Peoples collection hails from across the globe and includes everything from archaeological material, body adornment, everyday items and ceremonial objects, through to contemporary arts. Sadly, the museum also holds ancestral remains, a legacy of the horrific trade of human remains through the 19th and early 20th Century.”

It’s a situation that has sparked Zoe’s undeniable passion for the repatriation of cultural artefacts – not just seeing Tasmanian items returned home, but ensuring objects of significance belonging to other cultures find their way safely back across the oceans too.

Museums around the world are currently exploring a new approach to repatriation. It’s proving to be one that is exposing rifts in the global heritage community as well as nurturing strong relationships with First Nation leaders. The most successful projects to date include those that are largely led by the First Nation communities themselves – giving them full access to the collections, the time spent on the project, and the final fate of the objects.

An excellent example of progress is the Living Cultures initiative recently launched by the Pitt Rivers Museum in the UK. Spawned from a visit by a Maasai representative who was shocked to see the extent of the inaccuracies in the museums display of his culture, a new way to address this misinterpretation has been born. In this case, it is being led by traditional Maasai systems. The Maasai community are now identifying and describing artefacts and teaching the museum to attach the same significance to them that the Indigenous community does. The final resting place of the items lies firmly in the hands of the Maasai people.

The process itself has exposed many moments of pain. The realities of how some of the objects moved into the possession of the museum are shrouded in complexities that include violence, murder and theft. They are stories that clearly take a deep emotional toll on the community of origin and also challenge the museum staff themselves. Horrific stories attached to objects in your care can be wildly confronting.

At the heart of such projects sits trust and learning between stakeholders – values that Zoe believes can be applied here in Tasmania to help the local community light its own path forward. She is passionate about the repatriation of Tasmanian Aboriginal objects from overseas and, in turn, exploring possible avenues for redress.

Receiving a coveted Churchill Fellowship in 2013, Zoe travelled through Europe and the United States. “That experience was an amazing opportunity to explore how First Peoples collections are being treated overseas. The goal for me was to gather this knowledge and to potentially return home with new methods that might improve our practices here in Tasmania,” describes Zoe. “Along the way, I also discovered quite a lot of Tasmanian cultural material that we didn’t even know existed. And we have been working towards bringing some of that home ever since.”

Zoe explains that the process to repatriate objects from international collections isn’t as straightforward as one may think. “There are lots of different barriers,” she starts. “From large museums overseas not placing value on Tasmanian objects – they can be seen as just a drop in the ocean compared to other issues they are dealing with – through to legislative restrictions. There are often significant legal barriers to moving objects. Sometimes they can get around this by returning artefacts on permanent loan, however it doesn’t work in all instances.”

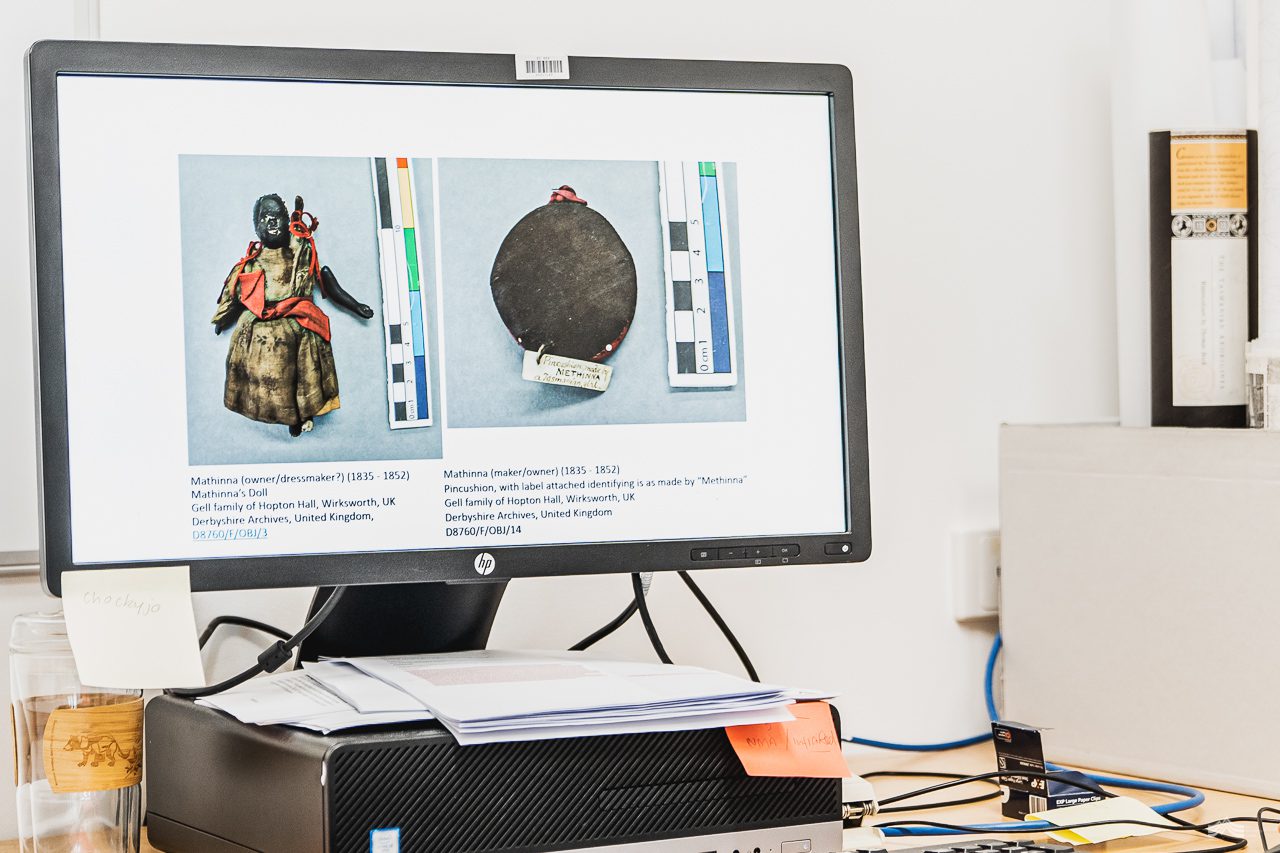

Two objects that have recently been uncovered are a pin cushion made by Mithina (Mathinna) and her small doll. “Mithina was born in 1835, daughter of Tawtara and Wunganip from the south west nation of Lutruwita,” explains Zoe. “They, like many others, were rounded up and sent to Wybalenna on Flinders Island in 1833. Both Mithina’s parents died in this exile camp. When Sir John and Lady Jane Franklin visited Flinders Island they took a liking to Mithina and adopted her, thrusting her into life at Government House. The story is often painted as the Franklin’s rescuing her, rather than Mithina being taken from her community and plunged into the unknown.”

Mithina lived with the Franklins for almost five years and was educated alongside the Franklin’s own daughter, Eleanor. “However when the Franklin’s returned to England in 1843 they left this little girl to the destitute Queens Orphan School,” continues Zoe. “Mithina’s life from then on was a tragedy. She was moved from the orphanage back to Flinders Island and then to Oyster Cove. All accounts indicate her life was very unsettled and lonely…she was repeatedly moved between different classes of society. It is said that Mithina drowned at about 17 years of age.”

“We came across Mithina’s doll and a pin cushion sewn by her in a local council archive in England,” nods Zoe. “It was the last place we’d expected to find something like that. It appears that the Franklin’s took them to England and they have been passed down through Eleanor who married into a local family in the area.” She continues slowly, “I feel quite emotional when I think about that little girl being deserted by the Franklin’s. The doll and the pin cushion are objects we are trying to have returned to Lutruwita (Tasmania) – objects that could be really important to shifting conversations here. I am sure their return would generate even more conversations about returning ancestral materials home.”

“The Tasmanian Aboriginal people were one of the first communities to campaign for the return of human remains,” explains Zoe. “To our community’s credit they have been at the forefront of the worldwide movement for ancestors scattered across the globe to be returned to their rightful homes. It’s something the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre continues to drive…the community very much wants to see these items of huge cultural significance resting back here in Lutruwita (Tasmania).”

The issue is a complex one and whilst most museums are moving forward, the change is slow. Repatriation is just one part of the problem. The second is what to do with the objects once they are returned home. “TMAG certainly feels like the appropriate space to tell the colonial story, but not necessarily the whole Tasmanian Aboriginal story,” notes Zoe. “We tend to put colonial history on a pedestal and pay little attention to the 40 000 years prior to that. Sometimes I can’t understand why people don’t show more interest in that…it’s quite amazing when you stop and think that we’ve been here for that long.”

“I think the Tasmanian Aboriginal community largely feel like we need our own space in which to tell our own story. Some form of cultural centre where the story belongs to us and is not told, or misrepresented, by others.”

Zoe is heartened that there is change occurring in Tasmania. “Historically – and quite ironically – TMAG and its precursor, the Royal Society Museum, are responsible for many acts that went against the wishes of First Peoples. Everything from the collection of spiritual and ceremonial objects to the removal of ancestral remains. It was typical of the time…so many practices that demonstrated absolute disrespect for local spiritual and cultural practices. In the past it was not uncommon for these objects and our people’s remains to also be the subject of global scientific exchanges.”

“Things are certainly changing as people are finding the courage to take responsibility for the past. Tasmanian Aboriginal remains were highly sought after for a period of time due to myths around extinction. There’s still a long way to go and many things to work through on many different levels. There are some amazing people working at TMAG to progress the collection…the likes of Dr Julie Gough and Liz Tew for example. We’ve been able to change the way Aboriginal culture is displayed and interpreted over the course of the past two decades and really begin to shift the perspective. Recently TMAG also appointed it’s the first ever Pacific Curator, Māori woman Keren Ruki.”

“People also assume that the Aboriginal community have a shared view on these matters, but that’s also far from the truth. The opinions are quite diverse.”

Whilst repatriation is a huge driver for Zoe, and the subject of her current PhD, she is also intently interested in how collections can revive and inspire cultural practice. “Ten years ago we saw the luna tunapri project inspire a new generation of shell stringers,” explains Zoe. “Shell stringing is an ancient Pakana tradition, the end product of which is beautiful necklaces. But it is so much more than that. It’s about the conversations and connections that occur during the collecting, cleaning and stringing of the shells. Those stories string together endless generations.”

The opalescent marina shell lies at the heart of the shell stringing tradition. It’s a symbol of community that rests loosely around Zoe’s own neck. “The colours of the marina shell reflect the ocean, the seaweed, the moon and the sky. They reflect our very ancestral connection to the land and seas.”

The luna tunapri project beautifully reconnected Tasmanian Aboriginal women with keepers of the shell stringing tradition. “A new generation of stringers now have these ancestral skills and will be able to continue the practice and share the narrative into the future…much like an unbroken string,” smiles Zoe.

A similar example continues to take centre stage in TMAG’s gallery. “Reviving the tradition of canoe building in Tasmania was very special,” says Zoe. “Canoes have been used to access Tasmania’s offshore islands for generations so that people could hunt and gather food. The exact materials used tended to vary from region to region, for example the type of bark may have differed, but the construction method was consistent.”

“It was the first time in about 170 years that a canoe had been built by our community using the techniques and materials of our ancestors,” describes Zoe. “To construct the canoe that now sits on display at TMAG, models that the museum has in its collection that date to the 1840s became very useful. Sea trials here on timtumili minanya (the Derwent River) demonstrated that the design was robust and canoe building is now becoming more common as the men continue to revive the tradition and extend it to contemporary artistic practices. That was a rewarding project and one that continues to link the collection directly to the community.”

Zoe reflects on the change that she’s seen across the past two decades. “Myself and many others have been trying very hard to change the conversation and to provide another perspective. Things are definitely changing but there is still a long way to go. Australia likes to think it’s leading the way, and indeed, it has been progressive in terms of returning ancestral remains but that’s where the conversation has stalled. We need to keep things progressing. For our future.”

“How I feel now?” asks Zoe. “I’ve always tried to work from a community perspective, but now I feel it’s time for us to be given back ownership of our cultural heritage including museum collections. It’s time to tell our history – and in the way that we want to tell it. The Tasmanian Aboriginal story is certainly not all about loss. We believe we’ve been here forever and there are many aspects that we want to celebrate about our culture.”

“It is my dream that we have our own Pakana community governed and operated space; a space that empowers a real Pakana museology – a place where there will be no question as to ‘who tells whose story, and to what audience’.”

Currently completing her PhD studies, Zoe has recently been awarded the 2021 Australian Academy of the Humanities’ John Mulvaney Fellowship. “A key component of both my studies and the fellowship is the Preminghana petroglyphs,” says Zoe. “Slabs of those special engravings were taken in the 1950s by the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery and in the 1960s by TMAG. Part of my work is focussed on the repatriation of these items to the Aboriginal community.”

The fellowship is named in honour of archaeologist John Mulvaney FAHA. Mulvaney himself visited north-western Tasmania in 1963, aware that TMAG had removed a large slab of the engravings from the area. “It is said that Mulvaney was ‘absolutely shocked’ by what he saw,” recounts Zoe. “The museum ‘had sawn off the face of the carvings’ and there ‘were bits of carvings lying all around, broken’.”

“Mulvaney’s outrage effectively stopped the Museum from cutting further panels out of the petroglyph site and led him to involve the Aboriginal Institute…to undertake extensive excavation and documentation of the site in 1969. Fast forward to 2019 and TMAG committed to repatriate the Preminghana petroglyphs. In February this year the museum issued a formal apology to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community for their treatment of ancestral remains.” Zoe finishes, “It’s been quite a transformation and one that I hope will pave the way for further repatriations in the future.”

References

https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/maasai-living-cultures