Vale Terence Klug

5 April 1943–19 November 2023

Every now and then a special soul weaves their way inextricably into the local community, becoming part of the very fabric that defines its core.

Terence Klug was one of those people.

Terence was born in Broken Hill in far western NSW. As a son of a mining engineer, his early years were peppered with intriguing stints across regional Australia. “I remember moving to the Northern Territory around age 10 so that my dad could take up work reclaiming the Northern Hercules Gold Mine,” recalled Terence. “When we arrived, the mine was full of water and he had to wait for the dry season to arrive before being able to really get stuck into getting the mine back up and running.” It was a lifestyle that quickly ingrained a drive for outdoor exploration into a tall, tanned and friendly lad. “A couple of years later I managed to fail Year 7 brilliantly,” nodded Terence. “I may have spent far too much time out tinkering with trucks and machinery rather than focusing on the books.”

Terence’s early academic wobble was just the impetus his mother needed to relocate the family. “Being one of just two women among 80 men, mum never liked the lifestyle in Pine Creek very much,” Terence explained. “She grasped the opportunity to pack us all up and move to Adelaide, making it clear it was time to concentrate on our education. But those early years spent in the outback school of life had very much shaped a practical path for me… I was strongly connected to the land. I went on to complete my training in agricultural science at Roseworthy Agricultural College, specialising in animal husbandry. I knew farming was intense, but I could also see the value in qualifications and was happy to study if it meant it was going to help get me where I wanted to go.”

As a young man Terence gained agricultural experience with the Mutooroo Pastoral Company, a sizeable sheep and cattle enterprise, and then later with a merino stud. “It was with that experience under my belt that I then accepted a job in Tasmania in the late 1960s,” explained Terence. “I distinctly remember that after having spent so many years working in hot and dry conditions that I found the cooler weather just wonderful. I threw myself into research work in Launceston involving trace element deficiencies in the soil and the appropriate selection of beef cattle.”

“Farming was always intriguing to me,” reminisced Terence. “My brother and I had a collection of dinky toys… farm models and animals. I remember my mother being very happy that we were using our imaginations.”

An introduction to the Agricultural Bank, the state’s specialist in rural finance, proved a turning point in Terence’s life. “In 1972 they offered me a posting to Flinders Island,” Terence smiled. “I think they could see that I had a good understanding of the challenges facing farmers and were confident in my ability to administer the war service scheme. My role as a financial management consultant subsequently opened the door to my very slow study of accountancy.”

In the early seventies the population of the largest island in the Furneaux Group was almost double that of today. “That was a wonderful time,” smiled Terence. “The community was dynamic and vibrant, with lots of young families and plenty of social activities going on. There were dances, badminton, tennis, film nights, local drama productions, barbeques on the beach, dinner parties and nights at the golf club. It was a lot of fun. The second solider settlement scheme was in full swing and agricultural productivity was going from strength to strength. I jumped right into life on Flinders and everything it had to offer.”

Flinders welcomed influxes of settlers under the Soldier Land Settlement Scheme following both world wars. As Terence explained, “Those that were interested could put their name into a ballot. If your name came up, you got a property… up to 800 acres.” He continued, “They each had boundary fences, a three-bedroom weatherboard house, a shearing shed and an all-purpose structure to house hay and machinery. There was no power back then though, so every property had a diesel generator. They were also given low interest loans to enable them to complete the sub-division, reticulate water and purchase farm tools and machinery… because a lot of people didn’t have money.”

A total of 85 returned soldiers settled on Flinders after World War II between the mid-1950s and 1972. Terence said, “They came from all corners of Australia, mostly aged in their 30s and 40s, with several blokes having zero farming experience. It not only drove agricultural development, but it also reinvigorated the social fabric of the Flinders community because they all had young families. More importantly, it was a real boom time for the island, creating new jobs and business opportunities and boosting the local economy.”

“Of course, not all the settlers were farmers or had strong business experience, so that’s where my role came in.” Terence continued, “It was my job to help manage 22 farms that had run into difficulty. Some families waited it out until commodity prices changed, whilst others elected to cash in their properties and leave the island. It was certainly challenging for some young families, and I spent many hours at kitchen tables working through figures and likely outcomes to help them make the tough decisions about their future.”

“Looking back, the entire settlement scheme proved to be a wonderful gift for the next generation. The multiplier effect was extreme and there are many families on the island today that are still working the farms of their parents or grandparents.”

“I’d always had an interest in the economic side of farming,” said Terence. “As time went on, I could really see that accounting was the most practical qualification for me to have. It proved to be something that I could utilise to help others find the best result for the situation they found themselves in.”

Terence’s foray into the world of accountancy is one he took seriously. “I studied diligently by distance and ended up completing a mixture of almost 30 units remotely. Funnily enough, the units didn’t end up meeting the formal requirements for admission to the Charted Practising Accountants of Australia.” He added with a grin, “Eventually I wrote to them and explained my experience. The reply said, ‘You’ve done enough son, we welcome you in.’”

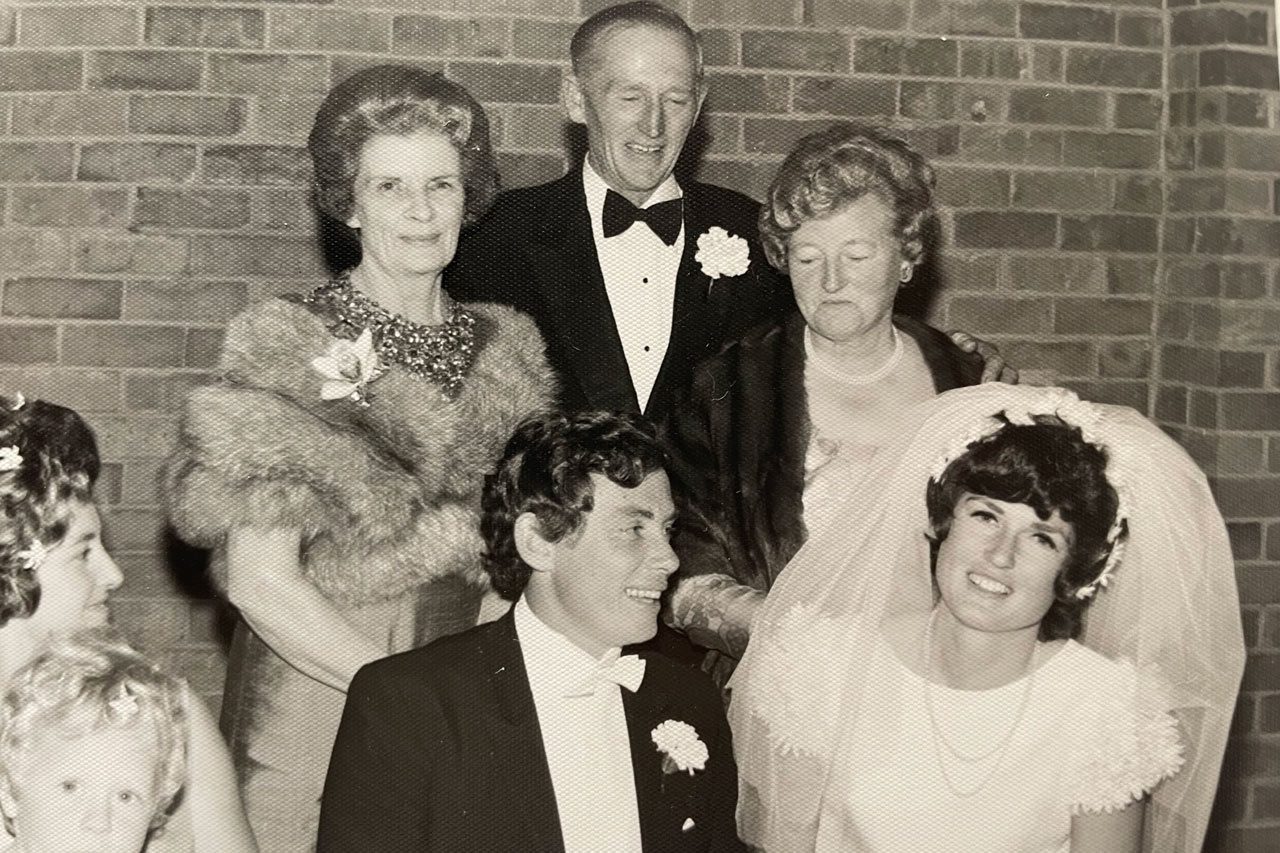

Terence met his wife June, a third-generation island girl, on the Flinders Island golf course. After a formal introduction at the club later that same evening, the couple were engaged and married within months. “I married her for her money, and she spent mine,” he joked, laughing. “We bought our first farm on Flinders, 200 hectares, in the mid 70s for $36,000. We shared a dream that we could run a farm of our own and were just waiting for the timing to be right.”

As his Agricultural Bank clients gradually wound down to just a handful, Terence was transferred to Hobart. “After a short stint in the capital, it didn’t take long for us both to want to return to the magic lifestyle on Flinders,” said Terence. “I’d finally completed all my accounting qualifications and could see a real need for the profession on the island,” Terence said. We were also keen to run our own farm too. It seemed like the right time to give it a go… the wool industry was booming.”

Embracing opportunity, 1980 saw the Klug’s pack up their four young daughters and head back to Bass Strait. “Around the same time, we were able to purchase some adjoining land,” explained Terence. “That meant we had a viable unit of 1000 hectares that was well suited to sheep farming. Even June’s old role in the medical practice became available again so things really seemed to be falling into place.”

What the Klug’s didn’t predict was the bottom falling out of the wool market in 1987. “We initially started with Polwarth sheep but could see the trend was moving towards finer wool,” recalled Terence. “We shifted towards Merino and then trialled converting some of the wool to yarn at Coats Patons in Launceston. I knew the manager there and he was happy to give it a go.”

It was an innovative move that sparked the beginning of Flinders Island Fleece.

Terence recognised the potential in boutique woollen products, likening the natural value that abounds on Flinders to that of the Scottish Shetland Islands, home to the famous Fair Isle knitwear. “Looking at my own wool that would sell for about $3 a kilogram, compared to $150 for a beautiful woollen jumper, I quickly realised the future was about value adding. It resulted in us employing over 30 home-based knitters in Tassie, and on the mainland, for more than ten years to create a unique range of woollen jumpers.”

It was a cottage industry that quickly benefited from Terence’s financial expertise. “Whilst traditional yarn is about 27-32 microns, we were producing yarn around 22 microns which was very soft against the skin. This improved our wool price to around $10 a kilogram.”

Flinders Island Fleece built a solid reputation for quality. “We mostly sold direct to our customers at trade fairs and agricultural shows across south-eastern Australia, but we also offered made to order garments,” explained Terence. “In addition, we created a range of yarn packs that included patterns and instructions so customers could knit designs themselves. Those were very popular.”

As the business grew, the Klug’s supplemented their income with Terence’s accountancy practice and June’s role at the medical centre. “Diversification has always been the key to survival on Flinders Island,” nodded Terence.

Like many family run businesses, Flinders Island Fleece hit the common quandary of whether to remain comfortable or increase its risk with a sizeable expansion. “There were solid indications that there was a growing demand for our products, but once we weighed up the financial risks, and the time involved we decided to leave things on a manageable scale. But not long after this decision, we were approached by a buyer from Canberra who loved the products and purchased the entire business lock, stock and barrel. It worked out very well all round.”

Not one to rest easy, Terence’s interests never stalled. In the mid-80s the Klug’s ventured into tourism, a move that saw the family managing holiday houses on the island. “We were one of the first to offer self-contained holiday homes on the island at a time when tourism here was only just taking off,” described Terence. “But I give all the credit to June. She was the one with the energy, vision and commitment. She puts a lot of hard work into creating beautiful spaces for visitors.” Laughing he added, “I’ve spent so many hours washing and ironing sheets I could probably run a laundromat!”

“I’ve always believed there has been a strong future for tourism on Flinders as long as it is managed carefully with the community’s interests front and centre.”

Indeed, Terence was a dedicated community volunteer during his time on the island, serving 16 years on the Flinders Island Council, including five as mayor. Intelligent and well spoken, Terence was a natural born leader. “Like all remote communities, Flinders has its challenges,” he explained. “Transport is a continual one. I battled for a long time to get the longer airport runway sealed to allow twin engine planes to come in. That probably took five or six years to get over the line, and then we had it done within 12 weeks of getting the nod. Having the surface re-engineered to receive up to 35 seaters is something that’s been a gamechanger. Likewise, shipping remains a top priority for Flinders residents. Lady Barron is a deep-water port and that’s been upgraded in recent years too, which is great news for farmers and the community.”

With gentlemanly modesty, Terence was quietly proud of the achievements of the local community. “I’m pleased there has been greater government support… solid investment in infrastructure including the school, the hospital, community halls and town water supply. We’ve also seen great progress by enterprises such as the Hydro who have transformed the delivery of power across the island with new generators, solar panels and wind turbines. What we have here now is a renewable energy hub that is world class.”

In 2022, as he contemplated entering his eighth decade, Terence’s mind showed little sign of slowing down. With a glint in his deep blue eyes, he remarked, “I certainly don’t work as hard as I once used to, but I’m still out on the farm every day. I’m lucky that three of our girls embraced farm life and are very capable operators who are all managing various properties across the island.” He added with a grin, “I’m just a gopher now… the girls give me my orders every morning and I just say, ‘yes ma’am’.”

Traipsing across the farm, aptly in the ‘Kluger’, Terence explained the property has been expanded over the years to include four and half farms across the east and west coast. “We got out of wool completely and switched our focus to prime lambs and Herefords and Angus cattle. They’re about 550-600 kilograms when they’re done. These are gentle breeds, and we talk to them a lot. One of the worst things I’ve ever experienced as a farmer was to shoot surplus stock back in the 1970s. That was certainly a shock to the system and one I never want to repeat. We’ve learned to work with the weather now, not against it. Adaptation is key.”

“The lifestyle on Flinders is fantastic and the locals are friendly and caring. It’s been a remarkable place to raise our family,” Terence finished. “I think it would be true to say that everything I’ve achieved here is the result of strong collaborative relationships and true partnerships with the community. That’s just island life.”

Warm thanks to the Klug family for sharing the historical images included above.

Warm thanks to the Klug family for sharing the historical images included above.

Terence’s family continue to operate three holiday properties on Flinders Island.

Allports Beach House, Green Valley Homestead and Echo Hills Cottage.